JENNY

When I first met Jenny, it was a process of illumination. Upstairs at the River Road coffee house, we pushed lace curtains back from the windows, searching for the right combination of light and shadow. I took one photo, and then another, as we chatted about her children, whose photos she was quick to pull up on the screen of her phone. “I used to model,” she told me, angling to face to the late afternoon sun. And gradually, as our conversation became more natural, she told me of her experiences with addiction as a mother, sister, daughter, and friend.

That afternoon, I returned to campus humbled, amazed at the confidence and clarity with which she had shared her story. But I didn’t think I’d see her again.

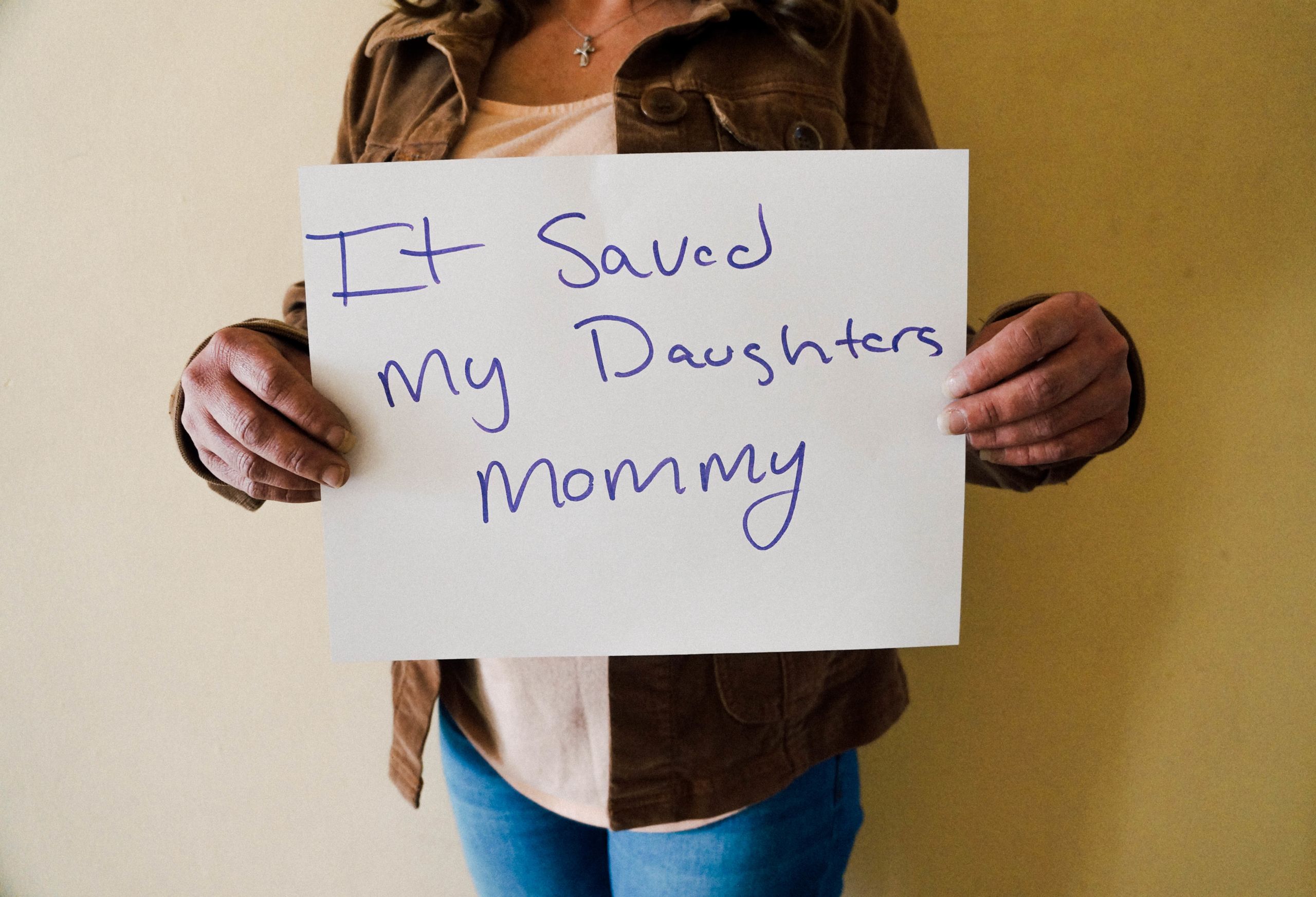

Working for Harm Reduction Ohio, a local non-profit, as a brand design intern, I became intimately aware of the needs and faces of harm reduction in Ohio’s Licking County. “Drug Policy Saves Lives,” read the landing page I helped to streamline, driving traffic to data shared through informative blog posts compiled by founder and former USA Today reporter Dennis Cauchon. Through the boxes of the opioid-blocker Naloxone that I helped label in the rented attic space, I began to understand to what degree.

I created a logo, and thought through an informational pamphlet. With founder Dennis and administrative assistant at the time Carole Robinson, I learned the most empathetic language to use to describe someone experiencing addiction. I began to meet local advocates, who would come to collect the packaged Narcan for distribution in their own circles of the recovery community. I attended a conference put on by the organization, that drew locals in recovery as well as family members of individuals experiencing addiction who traveled to Granville from across the state.

At the start of the following semester, I decided to work with the non-profit again to illuminate these voices. Writing and photographing locals in recovery, I collected several of their stories from their own perspectives, to increase awareness of harm reduction efforts through an anti-stigma campaign shared online.

Jenny was the first to volunteer.

She arrived at the HRO office on a brisk afternoon in April, accompanied by Billy McCall. Billy was a friend of hers made in day reporting, a rehabilitative alternative to incarceration in Licking County, who had been working for Harm Reduction Ohio at the time as well.

Jenny and Billy bonded as Billy began partnering with community members like Dennis Cauchon, to share insight from lived experiences with harm reduction in the area. For several months, he worked hard at bringing a safe injection site and needle exchange to Newark.

I had been nervous about working with individuals affected by addiction so directly. I met Billy through his mother, Patricia Perry, a local hard reduction advocate and organizer, who spoke at a community forum I attended hoping to learn more about the issue during my first year in Ohio at Denison University. While writing about how the opioid epidemic in Licking County had affected children and families uniquely, her insights were memorable even indirectly.

“Addicts have to help other addicts get clean,” Perry shared at an event in downtown Newark on April 25th, 2018. In front of a packed room, she spoke about her son Billy, and how he’d recently struggled with a relapse after several weeks clean.

“If I can’t help my own child, I can offer support to someone else’s,” she continued, explaining the motivation behind the Newark Homeless Outreach. To this day, Trish Perry stands outside the Licking County sheriff’s department every Saturday like clockwork, offering care packages of food and resources to individuals who are living on the streets or perhaps recently released. She has also made available harm reduction resources, which can be difficult to come by without a registered address or documented need.

Billy, of whom she spoke of with so much reverence, began to pursue recovery once again during my sophomore year. He came to speak at a class I was apart of focused in part on community outreach, breaking down adversity in the local environment in a way that students could consider. Something about the honest way he spoke about his experiences and his fierce determination seemed familiar, realized when he too spoke with love and admiration about his mom.

Billy helped me think through the anti-stigma project that winter and spring, working through the best way to phrase and approach questions I wanted to ask. He reached out to friends he’d accumulated in the local recovery community, and thought of Jenny for the project after remembering how he’d seen her animated personality quickly win over a room.

Jenny had her own ups and downs in the months that followed, yet she continued to pursue recovery until a community referral landed her at local women’s recovery house Awakening Lane. Founded in 2017 by local businesswoman Kerry Shea Penland, who also worked for a time as an entrepreneurship coach at Denison, the house became the focal point of my senior research when I explored how to further contextualize the knowledge I’d been gaining of recovery resources in the area.

On the first day I arrived at the yellow house in Newark to meet the women living inside, a familiar face bounced across the porch. Jenny had moved into Awakening Lane a few weeks earlier in July of 2019, and had quickly struck up friendships with her fellow residents during that time. Her recovery had progressed considerably through their friendship and support— she had reconnected with her children following some setbacks, and had secured employment at Aldi’s, a quality supermarket chain.

At Awakening Lane, Jenny returned to work with Harm Reduction Ohio and personal and community advocacy. She paid off old fines and found new ways to support her mental and emotional well-being. “I haven’t quite figured out what my higher power is. I’m still fine-tuning that. For a while it was the feeling in the rooms, I could grasp onto that— for a while I was my own higher power.”

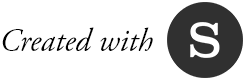

She celebrated Halloween with her children who had moved in with her mother down the street. Throughout her recovery, her love for her children has been a common denominator, pushing her to reassess and reevaluate where her priorities continue to lie.

During our first interview, I asked Jenny where in her life she found joy.

“Watching them play ball,” she responded without a second thought. Her son, who is 14, plays basketball, and her daughter is athletic as well. Attending their games, something she regrets missing out on, has been a highlight of becoming involved again with their lives.

“There was a moment in one of her games where she made the last shot. We were all there, with seconds left on the clock. No drug could ever bring that,” she shared, of the pride she felt towards her daughter, and herself for being there.

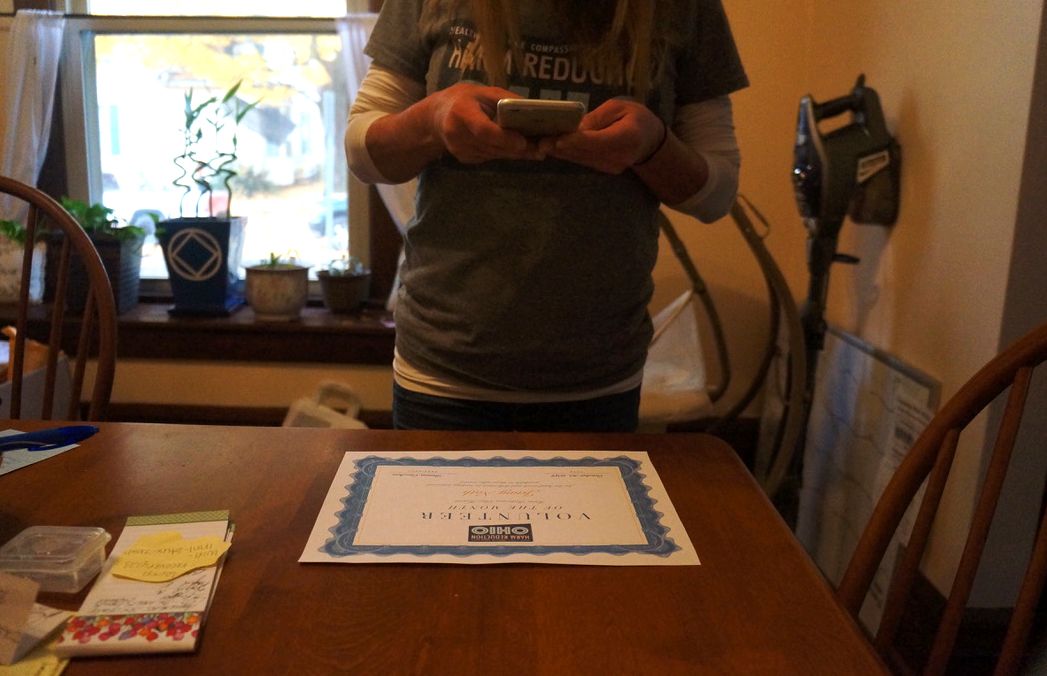

In November 2019, Jenny stood on her tiptoes at the Licking County Health Department’s monthly meeting, straining despite bad knees to make eye contact with the Health Board members who filled the room from behind the podium. “This is a photo of my children,” she says, voice clear and strong. “This is what recovery returned to me.”

As Jenny continues to speak, about a family wedding she attended over the weekend she never thought she’d see, her friends in the room nodded their support. Trish Perry, wiped at her eyes.

“She’s like a mother figure to me,” Jenny explained on the car ride over. “She understands what I’ve gone through and knows why I’ve been there.” Jenny met Trish through Billy McCall, whose advocacy efforts in the harm reduction community inspired her to begin to share her own story.

“Access to Narcan means survival,” Jenny concluded, voice clear and strong despite her small frame. At the Heath Board meeting, advocating in part for the grassroots efforts furthered by his mother, Jenny carried on Billy’s torch. Following her testimony, a grandmother paused before the microphone to collect herself, before sharing about her pregnant granddaughter whom Narcan had kept alive.

“Tell her about Awakening Lane,” Trish whispered to Jenny even before she’d finished speaking. “Are there any openings?” Jenny made a beeline for the woman after the meeting, phone once again opened and at the ready, to share her resources and connections.